Introduction

In the five years since the monumental 2020 presidential election cast an intense spotlight on election administration processes, the public servants from across the ideological spectrum who run our elections have weathered a deluge of threats, harassment, heightened stress, and increased scrutiny that does not yet show signs of abating.

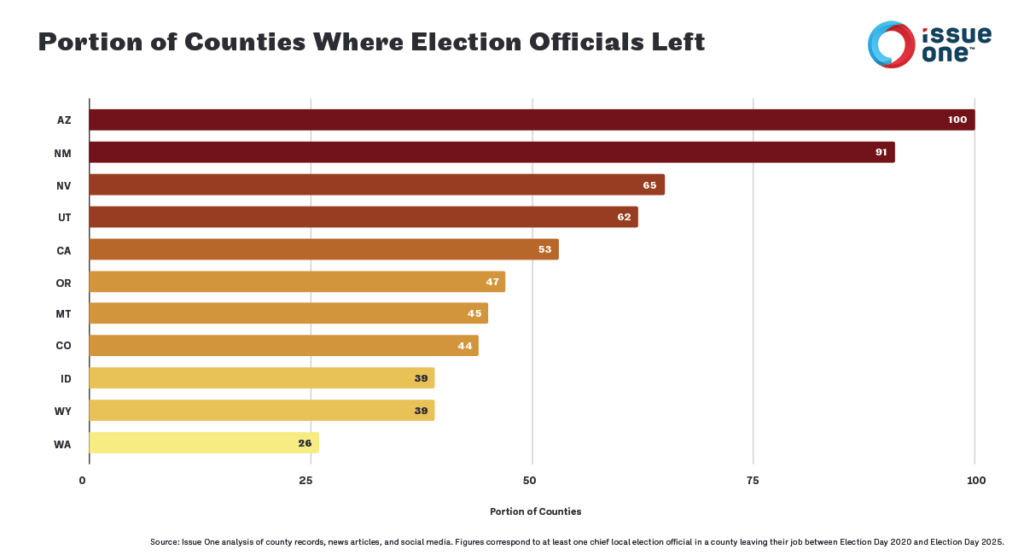

According to a new Issue One analysis that illustrates an alarming nationwide trend, 50% of chief local election officials in the nation’s Western states have left their jobs since November 2020, often leaving their positions partway through their terms for personal reasons.

This finding builds on our September 2023 study, which uncovered that roughly 40% of chief local election officials in the Western United States had left their positions since the 2020 presidential election — departures that left half of the region’s roughly 80 million residents with new officials running the 2024 elections in their communities. This study also reinforces findings by the Bipartisan Policy Center that turnover among chief local election officials has increased steadily since 2000 — and has been increasing faster since 2020.

The job of election administrators has never been easy. Election administrators — some of whom are elected and some of whom are appointed — are entrusted with the responsibility of shepherding the country’s system of democracy, working tirelessly and largely behind the scenes to administer free, fair, safe, and secure elections across the nation’s roughly 10,000 election jurisdictions, often without fully sufficient budgets, equipment, and other resources. Officials who are Democrats, Republicans, and independents work in close collaboration, diligently performing their duties in a system loaded with rigorous bipartisan checks and balances.

Since the 2020 presidential election, scrutiny on the once-obscure field of election administration has increased, partially because of a coordinated campaign of lies from President Donald Trump and his allies. This flood of false narratives has contributed to a surge of harassment and threats of physical violence, with one 2024 survey of election officials finding that nearly 70% of respondents had experienced intimidation, about 60% had experienced harassment, and about 30% had been threatened. This survey — which was conducted by the Elections and Voting Information Center (EVIC) at Reed College — found that just 22% of local election officials would encourage their own children to pursue careers in election administration, down from 41% in 2020.

While limited attempts at accountability against those threatening election officials may help deter misconduct, much more must be done to ratchet down the rhetoric and stop the spread of lies designed to erode public trust in the integrity of our elections.

Some efforts to achieve accountability have been waged, ranging from criminal convictions to massive payouts in defamation cases. Since the 2020 election, individuals from states including Alabama, Colorado, Florida, Indiana, Iowa, Massachusetts, Nebraska, New Hampshire, Ohio, and Texas have been convicted of threatening election officials. Two election workers in Georgia were awarded $148 million in damages by a jury that found former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani had defamed them. And media outlets Fox News and Newsmax each agreed to pay multimillion-dollar sums to voting machine company Dominion Voting Systems to settle defamation cases stemming from false claims about the 2020 presidential election.

Nevertheless, many veteran election officials are opting to head for the exits. While some counties and states appear to be more prone to turnover among local election officials, no state or county has been immune.

“Election officials now are wondering, why do I still do this if my office is going to get firebombed by a Molotov cocktail?” Republican Matt Crane, the former county clerk of Arapahoe County near Denver who now serves as the executive director of the Colorado County Clerks Association, told Colorado Public Radio last year after an elections office in a rural county in the state was firebombed.

“Now we have actual cases of people being threatened with harm, intimidated, and people having guns at drop boxes. It’s very concerning,” Derek Bowens, a nonpartisan election administrator in Durham County, North Carolina, told Issue One last year, noting that his county has invested in significant physical security updates, including bulletproof glass, ballistic doors, panic buttons, secure parking, and a separate exhaust system in the mailroom in case there are any hazardous chemicals.

Added Republican Kim Wyman, who previously served as secretary of state of Washington and as a senior election security advisor for the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) under President Joe Biden: “What we’ve seen in the last [few] years is that when the losing side of an election starts making accusations of voter fraud or voter suppression, this undermines their base’s confidence in the election… Sometimes it’s easier to say the election was rigged, that the referees threw the game, than it is to look at your own campaign and take ownership for maybe not doing the things you needed to do to get it across the line.”

When experienced election officials leave the field, they take with them immense amounts of institutional knowledge. Jurisdictions — large and small — also face significant financial impacts when recruiting, hiring, and training new people to fill these critical positions.

As this report makes clear, now is the time for political leaders at the local, state, and national levels to collectively work to dial down the rhetoric that has fanned the flames of conspiracy theories and violence against the public servants who keep our elections free and fair. Doing so would help retain dedicated, experienced people, who otherwise could be walking out the door with crucial institutional knowledge.

Specifically, as detailed in the recommendations section, governments at all levels should implement policies, programs, and partnerships to protect election officials from threats and harassment. Governments at all levels should also be doing more to financially assist cash-strapped jurisdictions, which have long had to stretch every dollar in their budgets to serve voters. And state and local election offices should increase their commitments to building the pipelines that will attract, recruit, and retain the next generation of election administrators. If swift measures are taken, there is still time for jurisdictions to strengthen the safety, security, and efficiency of the 2026 midterm elections.

Issue One echoes recommendations made last year by the Bipartisan Policy Center that “state and federal action is needed to address the chronic and emerging causes of turnover.”

Issue One Policy Director Michael McNulty stated: “Election officials are the unsung heroes of our democracy, and they need additional support now more than ever. High turnover rates are alarm bells we cannot ignore. Lawmakers and policymakers across the country at every level of government can help alleviate the effects of this alarming trend. And instead of sowing confusion or distrust, political leaders in both parties should stand up for the dedicated officials who ensure free, fair, safe, and secure elections in our country.”

Key Findings: Election Official Turnover in the West Illustrates a National Concern

Issue One selected the 11-state, Western United States for a case study on election official turnover for two main reasons.

First, this region contains two major presidential battleground states (Arizona and Nevada), as well as a mix of Democratic-leaning and Republican-leaning states.

Second, a case study of the West enables an apples-to-apples comparison across states, as elections in this region are typically administered at the county level by a single official, regardless of the geographic size or population of each county.

In this 11-state region, only in Arizona are election administration duties typically split between two officials in each county — an elected county recorder and an appointed elections director. (Both of whom were included in Issue One’s analysis.) In other parts of the country, a single state may have hundreds, if not thousands, of county, town, and municipal officials involved in election administration.

Local election officials in the West — most of whom are elected and some of whom are appointed — typically hold a title such as county clerk, county recorder, county auditor, county registrar of voters, or county elections director. Frequently, these officials are tasked with numerous responsibilities in addition to running elections, from taking minutes at meetings of their county commissioners to maintaining marriage, business, property, and Department of Motor Vehicle records.

Overall, the 11 states in this region — Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming — are home to roughly 80 million Americans, about 23% of the country’s population. Elections in this region are administered by 430 chief local election officials in 414 counties.

Since Election Day in November 2020, Issue One found that 50% of counties in the Western United States have experienced turnover in the chief local election official position — with at least one chief local election official leaving the job in 211 counties and at least two individuals leaving the job in 32 counties. In one Arizona county, five different people have held the role of elections director since the 2020 presidential election. All told, more than 250 individuals have left these critical election administration roles in Western states since November 2020.

While Issue One’s analysis shows that election official turnover peaked in nearly all of these states in the year following the 2022 midterm elections, in the year since the 2024 presidential election, 53 chief local election officials in the Western United States have left their roles — nearly as many as the 55 that left in the year following the 2020 presidential election.

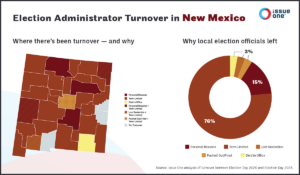

Nearly all of this turnover since November 2020 — roughly 76% — is attributable to people voluntarily leaving these jobs, not the result of losing a reelection contest (just 5%) or term limits (just 13%). In a handful of counties, chief local election officials died in office (2%) and in a few places (4%), county officials have fired or pushed out chief local election officials, or changed who in that county administers elections.

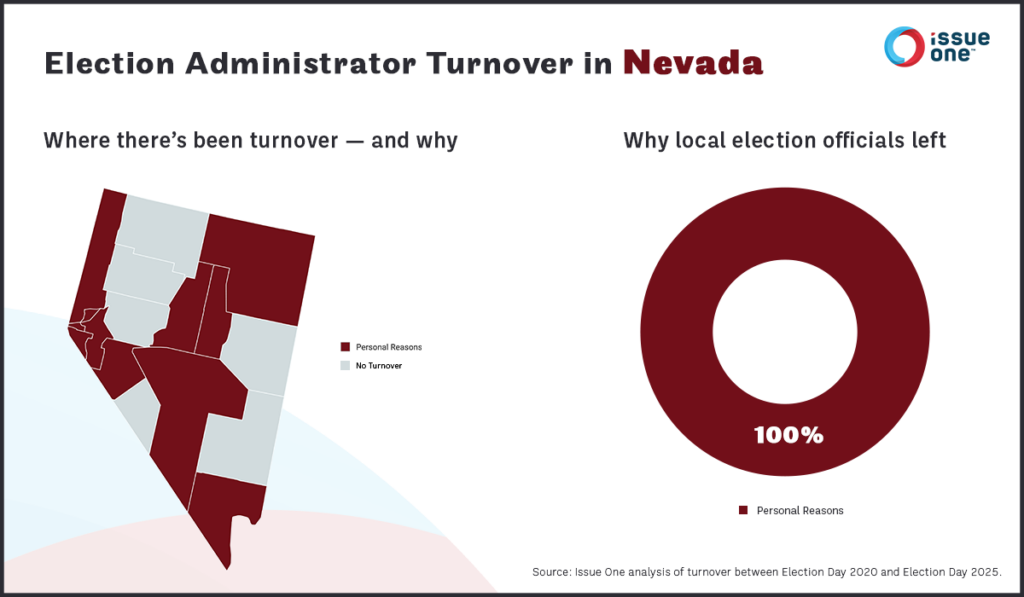

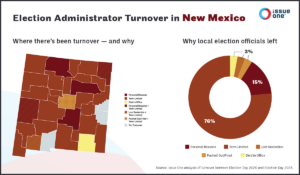

Only in New Mexico was most turnover since November 2020 due to term limits. New Mexico is unique among Western states in placing term limits on all county clerks, who serve as chief local election officials in the state. In the other 10 Western states, roughly 85% of local election officials who left their roles did so voluntarily — with 100% leaving for personal reasons in Idaho, Nevada, and Wyoming.

While turnover among election officials has been high across the entire region, Issue One found that it has been especially severe in presidential battleground states, counties with close margins in the 2020 presidential election, and populous counties. This suggests that chief local election officials in states and counties with close margins have experienced higher levels of scrutiny, stress, and harassment, resulting in their departure from the field.

- Battleground states: The presidential battleground states of Arizona and Nevada have experienced particularly high turnover. In Arizona, 100% of counties have experienced turnover among their local election officials, as have 65% of counties in Nevada.

- Counties with close margins in the 2020 presidential election: In the Western United States, battleground counties — where the 2020 election was decided by 5% or less — have been more likely to experience turnover than counties where the margin of victory exceeded 50%. Across the Western United States, 80% of counties with close margins in the 2020 presidential election have experienced turnover among their chief local election officials, while just 40% of counties where the margin of victory exceeded 50% have seen local election officials leave their jobs since November 2020.

- Populous counties: Issue One found that the turnover rate of local election officials differed by population size.

The smallest counties in the Western United States (those with populations of 10,000 or less) have experienced the lowest rate of turnover, while the largest counties (those with populations exceeding 500,000) have experienced the highest rates of turnover.

Across the Western United States, 60% of counties with populations exceeding 500,000 people have experienced turnover in their chief local election officials, while just 45% of counties with small populations have seen local election officials leave their jobs since November 2020.

This finding is in line with a 2022 EVIC survey that election officials in larger jurisdictions are more likely to report being concerned about abuse, harassment, and threats, and a 2024 EVIC survey finding that election officials in larger jurisdictions are more likely to consider leaving their job as a result of these threats.

State-by-State Key Findings

Here is a more detailed look at Issue One’s findings by state, which was based on the following methodology.

Turnover among chief local election officials in each state was analyzed between Election Day in November 2020 and Election Day in November 2025 by reviewing official government websites, election results, news articles, and social media postings. In a handful of cases, clarifying information was obtained through communication with the offices of local election officials.

During the time frame of Issue One’s study, two counties in California and three counties in Montana experienced changes in the office that holds chief local election administration responsibilities. Issue One classified these changes as a turnover in the person holding the chief local election official position.

Additionally, individuals who only held chief local election official responsibilities on a short-term, interim basis were not included in the overall tally of turnover in each state, though a few are referenced in the vignettes below.

Arizona

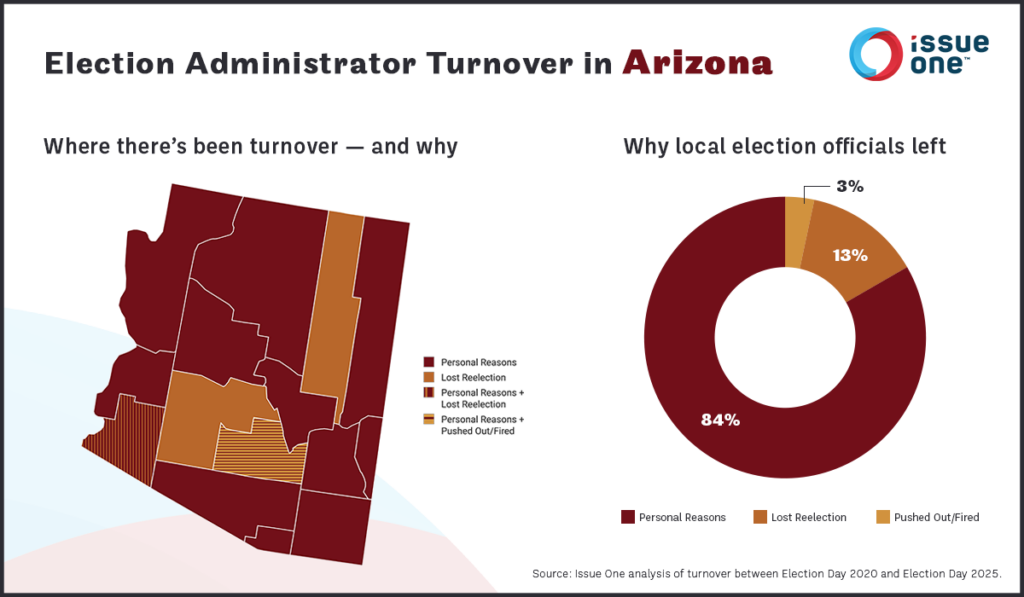

In the Western United States, Arizona is unique in that election administration duties are typically split between two officials in each county — an elected county recorder and an appointed elections director. (Both of whom were included in Issue One’s analysis.) Thus, roughly half of chief local election officials in Arizona are elected, and the other half are appointed.

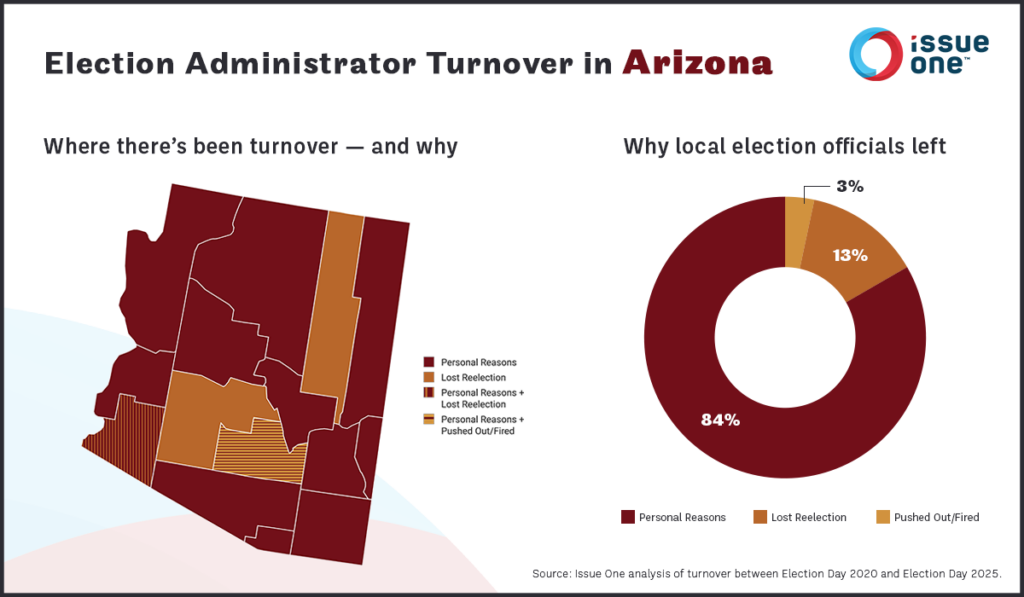

Of the state’s 15 counties, 100% have experienced turnover in at least one of the chief local election positions in the last five years. Just seven counties in Arizona have at least one election official whose tenure pre-dates the November 2020 elections. Of the 30 chief local election officials in Arizona who have left their positions since November 2020, 84% did so voluntarily for personal reasons, while about 13% lost reelection, and 3% were pushed out or fired (corresponding to one official). And of the 12 officials with designated terms who left for personal reasons, eight of them (67%) left before their terms were over.

The highest number of departures in Arizona occurred in the year following the 2022 midterm elections. But nevertheless, in the year after the 2024 presidential election, eight chief local election officials in Arizona left their posts.

Among those who have departed these roles since November 2020 is Republican Leslie Hoffman, who left her job as the county recorder in Yavapai County in July 2022 after nearly 10 years. She told one news outlet that increased threats and harassment contributed to her decision to leave, recalling that she received letters and emails with “very nasty comments.”

“When you’re being personally attacked, the character assassinations are terrible,” Hoffman lamented.

Notably, two counties in Arizona — Cochise and Pinal counties — have had extreme levels of turnover compared to all other counties included in Issue One’s study.

In Cochise County, in the southeastern corner of the state, the elections director role has been held by five different people in the last two and a half years, including one interim director.

Post-2020 turnover in this position began in February 2023 after Lisa Marra — who held the position for more than five years and was the president of Arizona’s association of local election officials — resigned as a result of a working environment she called “physically and emotionally threatening.”

Her resignation followed a stand-off with the county’s board of supervisors who illegally asked Marra to release ballots from her custody to conduct a hand count of all of the ballots.

Marra’s departure was followed by those of Bob Bartelsmeyer and Tim Mattix, who each held the role for less than six months.

Bartelsmeyer — who was hired away from La Paz County, Arizona, where he served as the elections director — departed the elections director role in Cochise County in September 2023 to return to La Paz County following an onslaught of stress due to being “ridiculed” and “intimidated” by election skeptics in Cochise County that exacerbated an existing health concern.

Mattix, who succeeded Bartelsmeyer, departed the role in April 2024 due to “personal family reasons.”

Following Mattix’s resignation, Marisol Renteria — who worked in the county’s information technology department — was appointed as the interim director. In May 2025, Melissa Avant was named the director of elections in Cochise County, and Renteria was later elevated to be the county’s deputy director of information technology.

Meanwhile, in Pinal County, in central Arizona, four people departed the county’s elections director role in the same number of years.

Post 2020-turnover in the county began in January 2021 when Michelle Forney, who held the role for more than five years, resigned to take a job in the office of Nevada’s secretary of state.

Forney’s departure was followed by the departures of David Frisk, Virginia Ross, and Geraldine Roll, who each held the role for less than seven months.

In August 2022, Pinal County announced that Frisk was no longer employed by Pinal County days after a programming error resulted in a ballot-printing error (which the office ended up correcting).

Ross, who had been appointed to the position after nearly 10 years as the county’s recorder, retired in November 2022, following the county’s certification of error-ridden election results, which she knew contained discrepancies and for which she nevertheless received a $25,000 bonus, as the news outlet Votebeat previously reported.

And Roll resigned in June 2023, citing a toxic environment where she was allegedly subjected to “ridicule, disrespect, intimidation, and attacks” on her reputation and ethics.

Following Roll’s resignation, the Pinal County Board of Supervisors voted unanimously to move the elections department under the oversight of County Recorder Dana Lewis, who conducted elections smoothly and without any major issues in 2024.

California

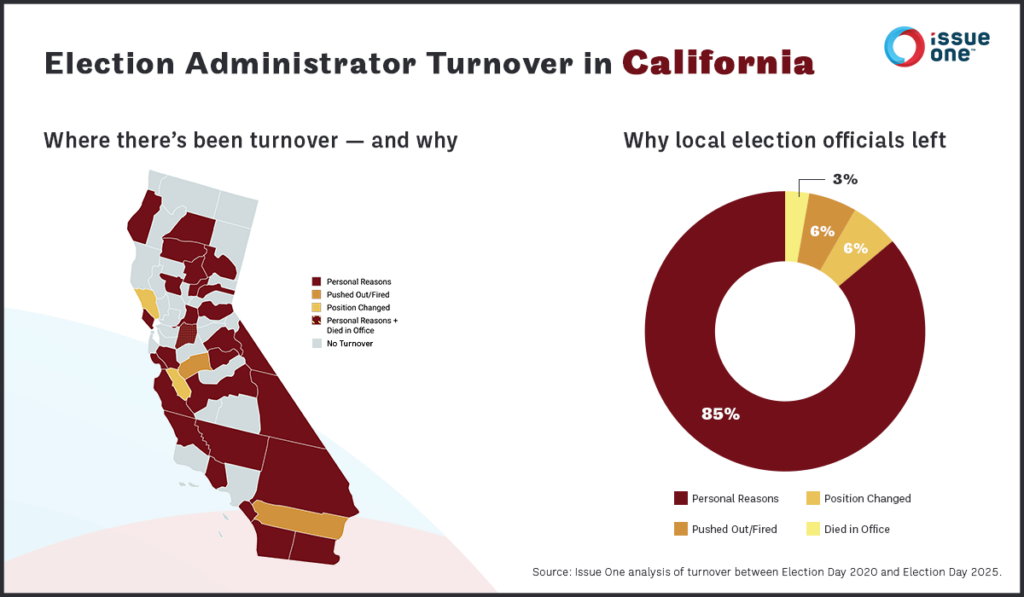

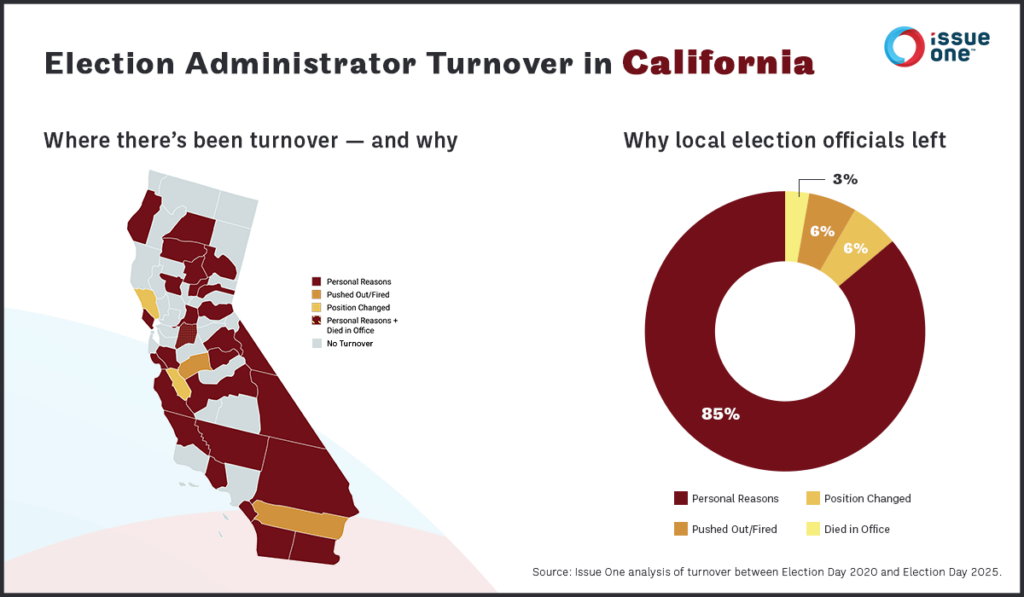

Nearly two-thirds of chief local election officials in California are elected; the rest are appointed. Of the state’s 58 counties, 53% have experienced turnover among chief local election officials in the last five years. And of the 36 chief local election officials in California who have left their positions since November 2020, 85% did so voluntarily for personal reasons, while 6% were pushed out or fired, 6% lost their position due to the responsibilities of election administration being reassigned to a different official, and 3% died in office (corresponding to one official). And of the 18 officials with designated terms who left for personal reasons, 11 of them (61%) left before their terms were over.

The highest number of departures occurred in the year following the 2022 midterm elections. But nevertheless, in the year after the 2024 presidential election, six chief local election officials in California left their posts, including in Marin County, north of San Francisco, where Registrar of Voters Lynda Roberts retired after serving for more than 10 years.

Five counties in particular have experienced significantly high levels of turnover in the five years since the 2020 presidential election. In each of these counties — Mono, Nevada, San Bernardino, San Joaquin, and Shasta counties — the chief election official position has been held by three different people.

Notably, in Shasta County in Northern California, this turnover happened rapidly — in less than a two-year period.

In May 2024, Shasta County witnessed the departure of longtime County Clerk and Registrar of Voters Cathy Darling Allen, who had held the role for nearly 20 years. She retired due to health concerns, worried that the stress from her role would worsen a new condition.

In her resignation letter, Darling Allen cited the high stress associated with election administration in the current environment and a need to invest in her health.

“I have been diagnosed with heart failure,” Darling Allen wrote. “An essential part of recovering from this diagnosis is stress reduction. As many election officials could probably tell you right now, that’s a tough ask to balance with election administration in the current environment. I feel strongly that my family must be my priority at this time. They have already sacrificed so much, and I must repay that investment by retiring and focusing on my health.”

Less than a year later, in April 2025, Darling Allen’s successor — Thomas Toller — also resigned for health reasons. “Based on the advice of my doctors, it has become clear to me that I cannot both focus on my health and continue to serve the citizens of Shasta County with vigor and undivided attention,” Toller wrote in his resignation letter.

In May 2025, the Shasta County Board of Supervisors appointed Clint Curtis — who has embraced fringe theories associated with the election denier movement — to be the county’s new clerk and registrar of voters.

Colorado

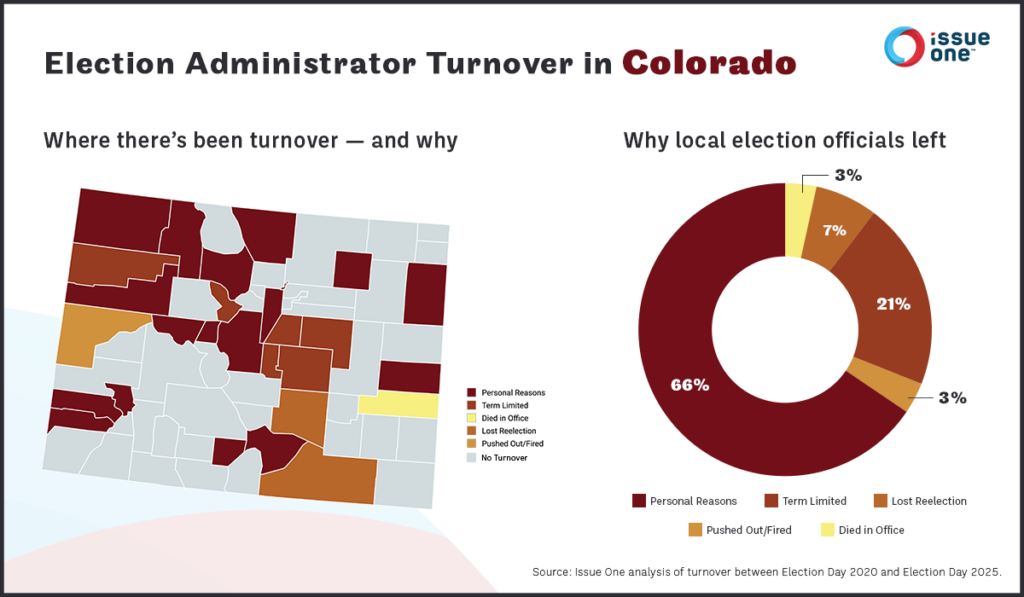

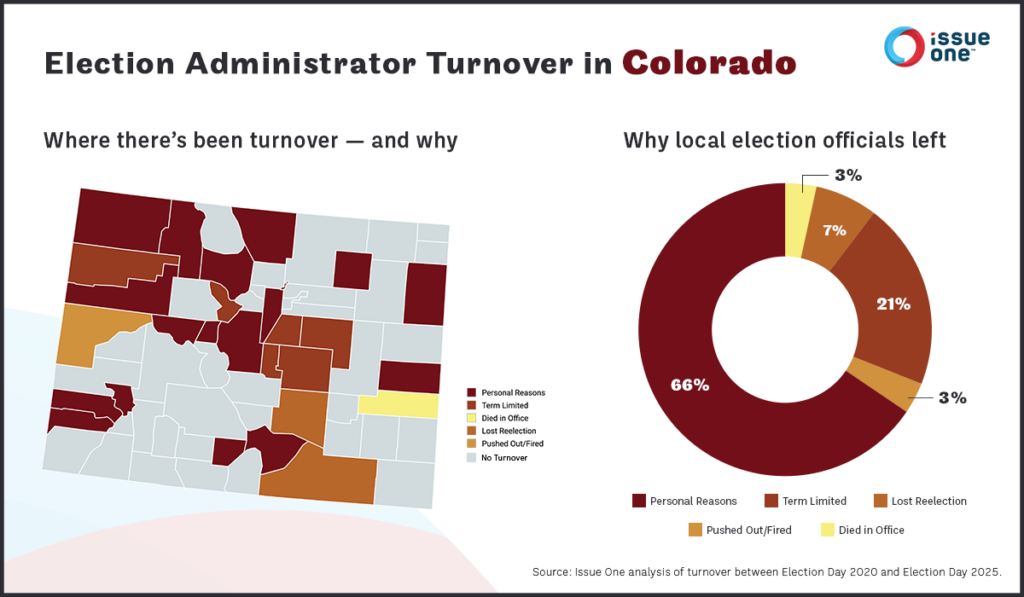

Nearly all chief local election officials in Colorado are elected, with about a quarter of elected chief local election officials facing term limits. Of the state’s 64 counties, 44% have experienced turnover among chief local election officials in the last five years. And of the 29 chief local election officials in Colorado who have left their positions since November 2020, 66% did so voluntarily for personal reasons, while 21% were term limited, 7% lost reelection, 3% died in office, and 3% were pushed out or fired (in each case, 3% corresponds to one official). And of the 17 officials with designated terms who left for personal reasons, eight of them (47%) left before their terms were over.

The highest number of departures occurred in the year following the 2022 midterm elections. But nevertheless, in the year after the 2024 presidential election, three chief local election officials in Colorado left their posts — in Dolores, Kiowa, and Yuma counties.

One of the officials who has left since November 2020 is George Stern, a Democrat who served four years as the county clerk and recorder in Jefferson County, a politically diverse county of more than 400,000 registered voters on the outskirts of Denver that is nicknamed the “Gateway to the Rocky Mountains.”

Stern told a local media outlet that navigating increased threats and stress in the wake of the 2020 election took a toll on both him and the staff who work in Jefferson County’s elections division.

“Clerks flew beneath the radar until 2020, and then we learned pretty quickly that anytime we responded to a threat, we would get many more,” Stern said. “What bothered me more than anything else was how it would affect the staff. You could physically see it taking a toll on them.”

Now, Stern’s successor — Amanda Gonzalez, who previously served as the executive director of Common Cause Colorado — is, like Stern, planning to leave the post after just four years in the role. She’s currently running in a competitive Democratic primary to be Colorado’s next secretary of state, a race that voters will decide later this year.

Notably, the area in Colorado that has seen the highest level of turnover since the 2020 presidential election is the consolidated city and county of Broomfield, which is located about halfway between Denver and Boulder. In Broomfield, three different people have held the role of chief local election official during the past five years.

Broomfield is the only county in Colorado where the chief local election official is appointed rather than elected. Consolidated city-counties such as Broomfield have unique autonomy over their local government which allows them to freely make modifications to the role, and Broomfield does not impose any specific term length or term limit on its chief local election official.

Following the 2020 presidential election, in January 2021, then-Clerk and Recorder Jennifer Robinson left her post after about three years, though the reasons for Robinson’s departure remain murky. In September 2020, Broomfield’s manager proposed releasing Robinson from her role, but the city council ultimately voted against doing so.

In May 2021, Erika Delaney Lew was appointed to be Robinson’s successor. She served for approximately one year before leaving the role to become a senior assistant city attorney for the nearby city of Thornton.

In September 2022, the Broomfield city council appointed Crystal Clemens as the jurisdiction’s next clerk, who brought experience as Broomfield’s deputy clerk and interim clerk.

Idaho

All chief local election officials in Idaho are elected. Of the state’s 44 counties, 39% have experienced turnover among chief local election officials in the last five years. And of the 20 chief local election officials in Idaho who have left their positions since November 2020, 100% did so voluntarily for personal reasons. And of the 20 officials with designated terms who left for personal reasons, 16 of them (80%) left before their terms were over.

One of the chief local election officials who opted not to run for reelection during this time was Phil McGrane, a Republican who left the role as county clerk in Ada County — Idaho’s most populous county, with about 500,000 residents — to run for secretary of state in 2022. McGrane prevailed in that race, defeating two state legislators in the GOP primary who denied the fact that Biden won the 2020 presidential election.

The highest number of departures among chief local election officials in Idaho occurred in the year following the 2022 midterm elections. But nevertheless, in the year after the 2024 presidential election, five chief local election officials in Idaho left their posts — in Benewah, Bonneville, Gem, Lemhi, and Lincoln counties.

Notably, the state’s smallest county by population size, Clark County — which is home to approximately 800 residents — has experienced the highest level of turnover among chief election officials in Idaho over the last five years, with four people serving in the role since the 2020 election.

In February 2021, Judith Martinez left the job of Clark County clerk after roughly two years in the role, moving out of the county.

Her successor — Tyson Schwartz — held the job of clerk for just eight months. When asked by the East Idaho News about the reason for his departure, Schwartz declined to comment, but he is now working as a teacher.

The next person to fill this job was Camille Messick, who, in June 2023, left after about 19 months for personal reasons. She told the East Idaho News that her kids needed more of her attention, and that she left because she couldn’t find a balance between work and her family responsibilities.

The following month, in July 2023, Clark County officials appointed Stephanie Stewart to the position. She has expressed optimism that this could be a career she keeps until she retires.

Montana

Most chief local election officials in Montana are elected. Of the state’s 56 counties, 45% have experienced turnover among chief local election officials in the last five years. And of the 33 chief local election officials in Montana who have left their positions since November 2020, 88% did so voluntarily for personal reasons, while 9% lost their position due to the responsibility of election administration being reassigned to a different office, and 3% lost reelection (corresponding to one official). And of the 23 officials with designated terms who left for personal reasons, 16 of them (70%) left before their terms were over.

The highest number of departures occurred in the years following the 2020 and 2022 elections, when nine chief local election officials departed their positions. Departures in the year after the 2024 presidential election nearly matched that level, with eight chief local election officials in Montana leaving their posts.

Notably, since the 2020 presidential election, three counties in Montana — Anaconda-Deer Lodge, Cascade, and Glacier counties — experienced a change in the office that holds chief local election administration responsibilities. In some instances, these changes were made in order to create a role solely dedicated to the time-intensive workload required for running elections.

All told, eight counties in Montana are tied for highest rates of turnover among chief local election officials in the state — Anaconda-Deer Lodge, Butte-Silver Bow, Cascade, Golden Valley, Lincoln, Petroleum, Sanders, and Yellowstone counties. In each of these places, three different individuals have held the role of chief local election official since the 2020 presidential election.

At least some of this turnover was driven by the impact of threats and stress.

Post-2020 turnover in Sanders County — which is home to about 13,000 people — began in February 2023, when Nichol Scribner resigned after serving as the county clerk and recorder, treasurer, and superintendent of schools for nearly a decade, citing increased threats and stress alongside ongoing health issues.

Following her decision to resign, Scribner told the Sanders County Ledger that she was “sad to be leaving the good people of Sanders County, however, the last year has been extremely stressful as I have ongoing health issues and have endured multiple threats.”

Her successor was Lisa Wadsworth, who held the position for about two years, deciding to retire at the end of 2024.

In a November 2024 special election, Alisa Garcia was elected to the role, and in December 2024, she was sworn in.

Meanwhile, in Lincoln County, which is home to about 20,000 people, the county’s post-2020 turnover began with election administrator Chris Nelson resigning in November 2020 after about two months on the job, a week after the 2020 presidential election. Various news outlets, including the Flathead Beacon, have reported that Nelson resigned for “personal reasons.”

After Nelson’s resignation, Paula Buff was tapped to be the county’s election administrator, but after roughly two years, she resigned in March 2023. The same day, two other staff members on her team also resigned from their positions.

The coordinated resignations were due to internal tension between the office and county commission, sparked by sitting commissioners reciting “national news narratives about election fraud,” according to former Lincoln County Clerk and Recorder Robin Benson, who was among the officials who resigned.

Benson noted that Buff left her position under “severe distress and anxiety” due to internal politics and tension.

Following the exodus of three officials, Melanie Howell was selected to serve as the election administrator in May 2023.

Nevada

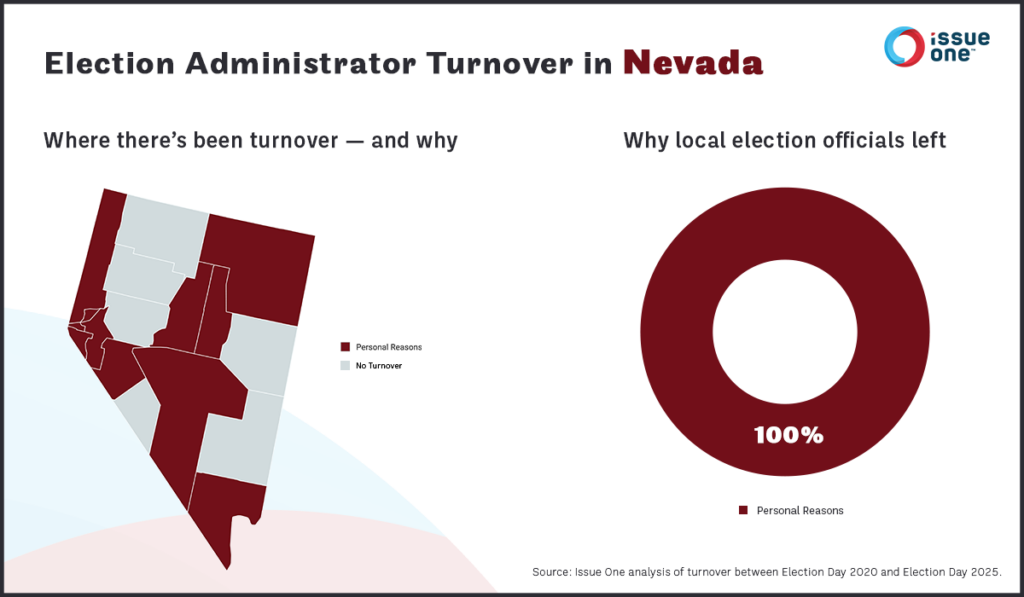

Nearly all chief local election officials in Nevada are elected. Of the state’s 17 counties, 65% have experienced turnover among chief local election officials in the last five years. And of the 13 chief local election officials in Nevada who have left their positions since November 2020, 100% did so voluntarily for personal reasons. And of the 10 officials with designated terms who left for personal reasons, eight of them (80%) left before their terms were over.

The highest number of departures occurred in the year leading up to the 2022 midterm elections. Remarkably, in the year after the 2024 presidential election, no chief local election officials in Nevada left their posts.

Among the officials who left their posts since the 2020 presidential election is Joe Gloria of Clark County, who left his appointed nonpartisan position as registrar of voters in the Nevada county that includes Las Vegas and is home to the largest population in the state in January 2023, after nearly 10 years.

Before Gloria left to take a new job with the Election Center, an association for election professionals, he shared his experiences of receiving threats with the Las Vegas Review-Journal.

Not only did Gloria receive threatening phone calls and emails, but so did his son (who shares his name). As a result, police had to come to the elder Gloria’s house on an hourly basis to ensure his family’s safety at the height of this harassment. Gloria said that these threats “had never been an issue for me when it was just me, but when my family became impacted, that’s when it did feel a bit different.”

Similarly, Republican Sandra “Sam” Merlino of Nye County, Nevada — who spent more than two decades as the county’s clerk — retired in 2022 due to the stressors of the scrutiny she faced following the 2020 presidential election.

Merlino told the Pahrump Valley Times that the accusations of election fraud, alongside the county commission’s decision to conduct the 2022 general election with a hand-count, contributed to her decision to retire before her term was up.

Another Nevada county that has seen notable turnover among its chief local election officials is its second-largest: Washoe County, which includes Reno. Since the 2020 presidential election, Washoe County has had four different people hold the chief local election official role, including one on an interim basis.

During the 2020 and 2024 elections, Washoe County experienced national attention due to being a swing county in a swing state, and the turnover in the county’s chief local election official position has largely been driven by individuals leaving for personal reasons, including dealing with increased threats and stress.

In July 2022, Deanna Spikula left her appointed nonpartisan role as the county’s registrar of voters after nearly five years, citing burn out caused by the workload, including responsibilities that were exacerbated by conspiracies about election administration.

“Elections have always had their challenges, but the challenges now are far above and beyond even what was seen in 2020,” she told the Reno Gazette Journal in 2022. “I don’t think I ever would have imagined that elections would get to this level of intensity and difficulty in just being able to perform your normal functions without harassment.”

Spikula’s successor, Jamie Rodriguez, left the role in March 2024 after less than two years on the job. She told the Reno Gazette Journal that she needed “better work-life balance” due to the immense amount of time she had been working per week.

After Rodriguez left, Cari-Ann Burgess — who had been the office’s deputy registrar — served as the interim registrar of voters, but she was in that role for less than a year. She was terminated in February 2025, and is currently in a legal battle with Washoe County, alleging a toxic work environment, coercion, and retaliation.

After terminating Burgess, the Washoe County Commission appointed Andrew McDonald, its deputy registrar, to be registrar of voters. McDonald has also previously served as an assistant registrar of voters in Clark County, Nevada, and San Diego County, California.

New Mexico

All chief local election officials in New Mexico are elected. Of the state’s 33 counties, 91% have experienced turnover among chief local election officials in the last five years. The vast majority of this turnover is due to the fact that New Mexico implements term limits on the county clerks who serve as chief local election officials, with individuals being prohibited from serving more than two consecutive four-year terms.

Of the 34 chief local election officials in New Mexico who have left their positions since November 2020, 76% did so due to being term limited, 15% did so voluntarily for personal reasons, 3% lost reelection, 3% died in office, and 3% were pushed out or fired (in each case, 3% corresponds to one official). And of the five officials with designated terms who left for personal reasons, three of them (60%) left before their terms were over.

Among the 11 Western states in this report, New Mexico stands out as having the highest number of departures during the year following the 2024 presidential election. During that period, 17 chief local election officials in New Mexico left their posts, with 14 of these officials being term limited and unable to run for reelection in 2024.

The New Mexico county that has experienced the highest levels of turnover since the 2020 presidential election is Torrance County, a region of about 15,000 people to the southeast of Albuquerque, where three individuals have held the job of county clerk — including one person who held the job twice.

Linda Jaramillo was term limited at the end of 2020. Yvette Otero was elected to succeed Jaramillo in 2020, but after roughly two years, she was removed from her role by the Torrance County Board of County Commissioners following an ethics scandal during which the commissioners accused Otero of missing work and abandoning her role.

Linda Jaramillo was then appointed to fill the position in an interim capacity between January 2023 and December 2024, and she did not run to be elected for the following term.

In November 2024, voters selected Sylvia Chavez, who had previously served as the county’s deputy clerk, to take over the job.

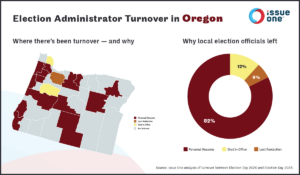

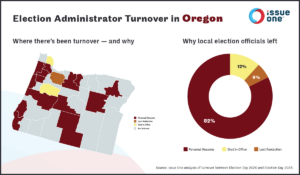

Oregon

Most chief local election officials in Oregon are elected. Of the state’s 36 counties, 47% have experienced turnover among chief local election officials in the last five years. And of the 18 chief local election officials in Oregon who have left their positions since November 2020, 82% did so voluntarily for personal reasons, while 12% died in office, and 6% lost reelection (corresponding to one individual). And of the 12 officials with designated terms who left for personal reasons, seven of them (58%) left before their terms were over.

The two Oregon county clerks who died in office during this time — Columbia County Clerk Betty Huser and Linn County Clerk Steve Druckenmiller — each passed away after having served more than three decades in their roles.

The highest number of departures occurred in the year following the 2022 midterm elections. But nevertheless, in the year after the 2024 presidential election, three chief local election officials in Oregon left their posts — in Lake, Lane, and Wasco counties.

To highlight the challenges that local election offices face, the Oregon Elections Division commissioned EVIC at Reed College to research such experiences. In June 2023, EVIC released the “Oregon County Election Staffing Research Study,” which found that many local election officials reported high levels of stress and burnout as a result of the political environment surrounding election administration. Many also reported a desire to leave the profession.

The report noted that “a disheartening number of [county] clerks and staff shared they were just holding on and debating whether they could continue, given this personal stress.”

While many interviewees shared that they took pride in the work they do, they also pointed to increased demands and long hours as drivers that might cause them to depart the profession. Some shared that their personal responsibilities at home — such as being a caregiver and partner — have to be put on pause while they dedicate their whole self to elections.

Among the study’s suggestions was that more competitive pay would help improve staff recruitment and retention. “Recruiting younger workers into election administration is critical to supporting succession planning,” the report noted.

The Oregon county that has seen the most turnover since the 2020 election is Lane County, which is home to about 380,000 people and stretches from the county seat of Eugene to the Pacific Coast — with three people holding the chief local election official position since the 2020 election. Despite the transitions, Lane County officials have ultimately replaced one long-time elections administrator with another highly experienced one.

In August 2022, Lane County Clerk Cheryl Betschart stepped down after more than 12 years on the job. Her successor — Dena Dawson, who previously ran elections in multiple jurisdictions in Colorado and Nevada — left after just two years as clerk to take a big promotion, becoming Oregon’s elections director. Then, in July 2025, Lane County hired Tommy Gong, an election administrator with more than 22 years of experience, to replace Dawson.

“Conducting elections is a noble profession,” Gong told Issue One last year as part of our “Meet the Faces of Democracy” interview series. “Many people find out that they really love elections, and they do have the passion to stick with it for as long as they can.”

Utah

All chief local election officials in Utah are elected. Of the state’s 29 counties, 62% have experienced turnover among chief local election officials in the last five years. And of the 21 chief local election officials in Utah who have left their positions since November 2020, 90% did so voluntarily for personal reasons, 5% lost reelection, and 5% were pushed out or fired (in each case, 5% corresponds to one official). And of the 19 officials with designated terms who left for personal reasons, nine of them (47%) left before their terms were over.

The highest number of departures occurred in the year following the 2022 midterm elections. In the year after the 2024 presidential election, just one chief local election official in Utah left their post — in Daggett County.

Three counties in Utah — Cache, Utah, and Washington counties — have had more extreme turnover than the rest of the state since the 2020 presidential election, with three people holding the chief local election official position in each of these counties during this time period.

In Utah County, the second-most populous county in the state and home to the city of Provo, Republican Amelia Powers Gardner left the role as county clerk after about two years, in April 2021, after being elected as a county commissioner.

Josh Daniels, the county’s deputy clerk/auditor, was elected to replace Powers Gardner in May 2021. Daniels, also a Republican, served as clerk for about a year and half, through the end of his former boss’ term in December 2022. He chose not to run for reelection.

In a 2023 interview with Issue One, Daniels said that his decision not to run for reelection was driven “largely because of the political dynamic.” He said that the internal politics within the county made his job “difficult because [elected political officials] were giving credence to false and misleading election conspiracies and turning the administration of elections into a political issue.”

Republican Aaron Davidson took office in January 2023 after being elected to the role in November 2022.

Washington

All chief local election officials in Washington are elected, though just a few counties place term limits on chief local election officials. Of the state’s 39 counties, 26% have experienced turnover among chief local election officials in the last five years. And of the 10 chief local election officials in Washington who have left their positions since November 2020, 70% did so voluntarily for personal reasons, while 20% lost reelection and 10% were term limited (corresponding to one official). And of the seven officials with designated terms who left for personal reasons, three of them (43%) left before their terms were over.

The highest number of departures occurred in the year following the 2022 midterm elections. Remarkably, in the year after the 2024 presidential election, no chief local election officials in Washington left their posts.

Of the 10 counties in Washington that have seen turnover among their chief local election officials since November 2020, none have experienced more than one change.

The Washington county that has most recently seen its chief local election official switch is Whatcom County, which is home to about 230,000 people and stretches along Washington’s northern border with Canada from the county seat of Bellingham on the Pacific Coast to the North Cascades mountains.

There, Diana Bradrick opted against running for a second term as auditor, after running unopposed for the role in 2019. Her successor — Stacy Henthorn — won an unopposed race to be auditor in November 2023.

Wyoming

All chief local election officials in Wyoming are elected. Of the state’s 23 counties, 39% have experienced turnover among chief local election officials in the last five years. And of the nine chief local election officials in Wyoming who have left their positions since November 2020, 100% did so voluntarily for personal reasons. And of the nine officials with designated terms who left for personal reasons, four of them (44%) left before their terms were over.

The highest number of departures occurred in the year following the 2022 midterm elections. In the year after the 2024 presidential election, two chief local election officials in Wyoming left their posts — in Carbon and Sublette counties.

Carbon County is home to about 14,000 people in the south-central part of the state. There, Republican Gwynn Bartlett stepped down as clerk in January 2025 to assume new duties as a county commissioner. And in the western part of the state, Sublette County is home to less than 10,000 people. There, Carrie Long left the role as clerk in June 2025 due to moving out of the county.

One of the other chief local election officials who left their position since the 2020 election is Republican Mary Grace Strauch, who retired in December 2022 after 38 years as the Washakie County clerk.

When the Northern Wyoming News asked Strauch why she was retiring, her answer was that as distrust in election results had risen in recent years, people increasingly began to question the work of people like her and that she simply was no longer interested in being involved.

A decrease in the public’s trust was also noted by Republican Campbell County Clerk Susan Saunders when she retired in December 2022, after 28 years on the job.

Of the nine counties in Wyoming that have seen turnover among their chief local election officials since November 2020, none have experienced more than one change.

Recommended Solutions: What Can Be Done Now to Build a Stable and Resilient Elections Workforce

Election officials are among the unsung heroes of democracy, working tirelessly — and frequently thanklessly — behind the scenes to administer elections that are safe, secure, free, and fair. In recent years, this profession as a whole, as well as individual election officials, have been baselessly vilified, threatened, and harassed. At the front lines of local government, election officials are acutely vulnerable to threats of political violence.

Many in the election administration community have been perplexed by the Trump administration’s embrace of costly unfunded federal mandates and structural hurdles that make voting more difficult for Democrats, Republicans, and independents alike.

Political leaders should be easing the burdens on election officials, not attempting to undermine our elections processes. Thankfully, there is still time between now and the 2026 midterm elections for political leaders at the local, state, and national levels to collectively support election officials.

In the months ahead, leaders across the country and across the political spectrum must not only work to increase resources and structural support for election officials, but also lower the temperature of political rhetoric that has too often fanned the flames of conspiracy theories, as well as harassment and threats of violence against election officials.

Lawmakers and policymakers across the country must stand with election officials as they face new stressors and an onslaught of threats and harassment. At the same time, jurisdictions across the country should invest in strengthening this core pillar of American democracy to ensure that all eligible voters can continue to participate in safe and secure elections.

To uplift the election administration profession and help curb the exodus of experienced election officials, jurisdictions large and small can take concrete steps to 1) protect election officials, 2) recruit the next generation of election administrators, and 3) retain and support them for years to come.

1. Protecting Election Officials

America’s election infrastructure is designated as “critical infrastructure”; protecting election officials should also be a national priority. Without safeguards against threats and harassment, the country risks continuing to lose experienced administrators who are essential to running free, fair, safe, and secure elections.

In 2021, in the wake of the contentious 2020 election and Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol, the federal government prioritized its commitment to protecting election officials by establishing a new Election Threats Task Force within the Department of Justice. This task force received more than 2,000 tips about threats against election workers, and these cases led to 100 investigations and 15 convictions. However, the status of the task force is currently uncertain, as the Trump administration has aggressively scaled back election security and accountability structures — raising concerns about its potential dismantling in an environment of increased threats.

Political leaders — state and federal officials alike — should reaffirm their support and commitment to protecting election officials and condemn harassment and threats against them.

Additionally, states should invest in increased resources to support local election officials in strengthening protections for their offices. This includes resources to improve physical security measures as well as to strengthen the monitoring and mitigation of threats that circulate both online and in person.

Congress should also follow the lead of states in passing legislation to prevent doxxing of election officials to further strengthen protections for those in this important profession.

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 35 states have criminalized intimidation and/or interference with election workers. Meanwhile, six states have criminalized doxxing election officials’ personal information online, and 10 states allow election workers to keep their addresses and other personally identifiable information confidential.

All election administrators deserve this type of protection and should be able to do their jobs without fear of threats, harassment, or harm to themselves, their offices, or their families.

2. Recruiting the Next Generation of Election Administrators

Buttressing the pipelines that attract and retain election officials is also a critical step to fortifying our nation’s elections infrastructure.

Where resources are available, states and local governments should implement programs that promote the next generation of election administrators. Dollars spent investing in the future of this critical profession will pay dividends for years to come and help build staff capacity in local election offices.

Many local election officials have said that it has become increasingly challenging to hire people, largely because applicants lack experience in election administration. Steps can, and should, be taken now to help abate this issue.

One state in the Western United States — Arizona — offers an example of how other jurisdictions can leverage investments in programs to build experience among, and attract new, election administrators.

In Arizona, the County Election Administration Fellowship was piloted in 2024 through the secretary of state’s office. This fellowship program placed college students and recent graduates in county election offices for five months, a model similar to AmeriCorps. Participants received a $15,000 stipend for their work supporting local election offices, provided extra hands-on support, and received a certificate upon completion of the program.

After the election, researchers found that this program was successful in increasing confidence in election administration, increasing the number of young adults interested in working in county election administration, and developing further capacity in county election offices by addressing staffing needs.

Such innovations should be regularly implemented and improved upon.

3. Retaining and Supporting Election Officials

Alongside recruiting the next generation of election administrators, legislators, civil society, and others in the election administration ecosystem should work together to support the retention of election administrators at the local level by limiting the burdens that are placed onto local election offices.

Legislators and courts should limit unnecessary and last-minute changes to election law and procedures that increase the workload of election administrators, whose work can be upended and disrupted by such changes close to when elections are conducted.

Additionally, federal and state legislators should avoid imposing mandates that change election procedures without providing funding to implement such changes.

For example, a proposal known as the SAVE Act would require voters to provide documentary proof of citizenship each time they register to vote, even though states already have systems in place to verify voter identity and confirm citizenship status. Individuals who are not U.S. citizens are ineligible to vote in elections, and noncitizens who attempt to vote face tough penalties — including steep fines, prison time, and deportation. These stiff penalties serve as a strong deterrent against illegal voting.

In a letter to Congress in March 2025, election officials — some of whom are members of Issue One’s Faces of Democracy campaign — expressed concern over the SAVE Act, noting that these changes to procedures would “represent a major administrative undertaking that would be shouldered entirely by local election offices.”

Another way that the workload of election administrators can be reduced is through, where feasible, consolidating elections — combining local and special election dates with federal and state elections.

A 2025 report from the Bipartisan Policy Center found that in the average state, a typical chief local election official administers 2.1 elections each year. No matter the size of an election, election administrators prepare for elections with routine responsibilities — spanning the gamut of testing equipment, training poll workers, and communicating with voters, for example. Consolidating the dates of elections could improve cost efficiency and temper the workload of election administrators.

Additionally, states and local jurisdictions — as well as individual election officials — can work to strengthen professional associations for election administrators, which are important arenas for providing resources, sharing information, and furnishing mentorship opportunities. As the Election Center and Coalition of Election Association Leaders has noted, state associations of election officials often play a big role in promoting collaboration and community within the profession. As Faces of Democracy campaign member Wendy Sartory Link, the supervisor of elections in Palm Beach County, Florida, recently told Issue One: State associations “have people who understand what you’re going through, and they know what you need.”

To bolster and strengthen the election administration workforce, civil society groups should work to elevate their stories and experiences through, for example, storytelling and recognition campaigns, community events, and partnerships with trusted local leaders. By humanizing officials and showcasing their professionalism, these efforts can boost trust in election officials and highlight their heroic endeavors that uphold democracy.

Tarang Mishra contributed to this report.