Introduction

Experienced congressional staffers are vital for the functioning of Congress, but for too long, Americans from all social and economic backgrounds haven’t been able to equally serve in these key roles.

Washington, D.C., is among the most expensive cities in the country, and cash-strapped congressional staffers frequently share horror stories about their economic distress and tips for stretching their dollars — from living with multiple roommates to working multiple side hustles to relying on free food at receptions on Capitol Hill to racking up credit card debt between paychecks. Providing fair salaries would make it possible for people from all social and economic backgrounds to work for Congress and live in the nation’s capital. Indeed, fair salaries are a critical step in ensuring that the federal legislature can be a place where congressional staffers are as diverse as the country itself.

Staffers play crucial roles in the daily operations of Congress. They are responsible for handling inquiries from the public and the press, crafting policy, conducting investigations, and advancing legislation. Providing staff with adequate financial incentives and opportunities for advancement reduces turnover, preserves valuable institutional knowledge, and reduces the influence of lobbyists and special interests.

In recent years, congressional leaders have implemented changes designed to boost congressional staff pay and retention. This report illuminates how these changes are, in fact, making meaningful differences for congressional staffers and strengthening the economic well-being of junior staffers on Capitol Hill. It also outlines additional measures that can be adopted to further ensure that Americans of all socioeconomic backgrounds are able to thrive in these roles in the legislative branch of government.

Among the highlights of Issue One’s new analysis are the following findings:

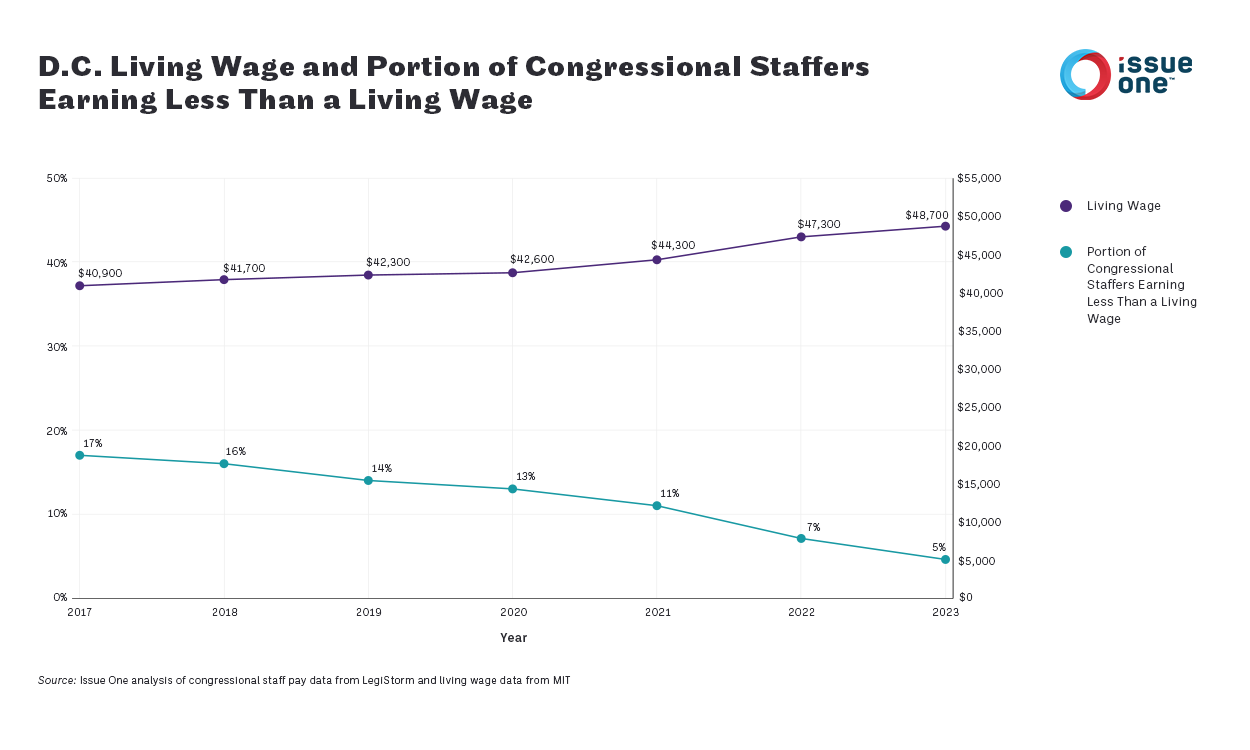

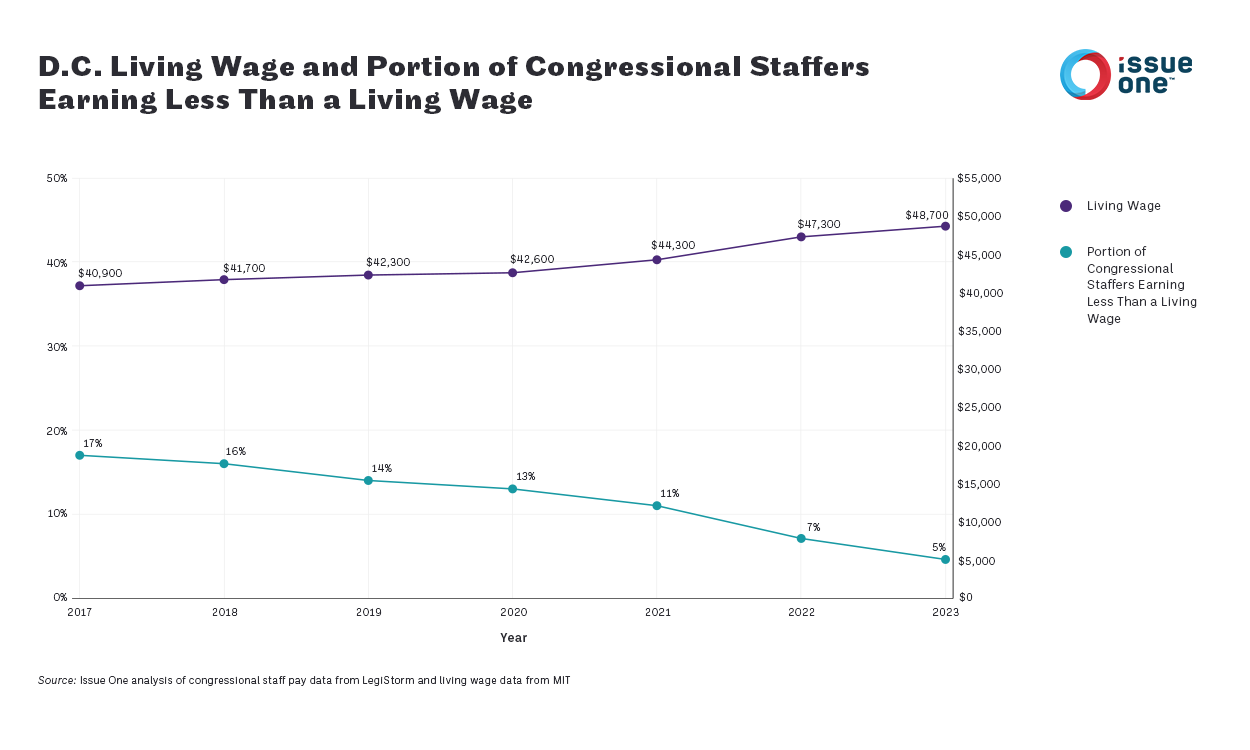

- The salaries of the lowest-paid staffers on Capitol Hill have generally been improving in recent years. In 2020, roughly 13% of congressional staffers made less than a living wage. In 2023, just 4.6% did.

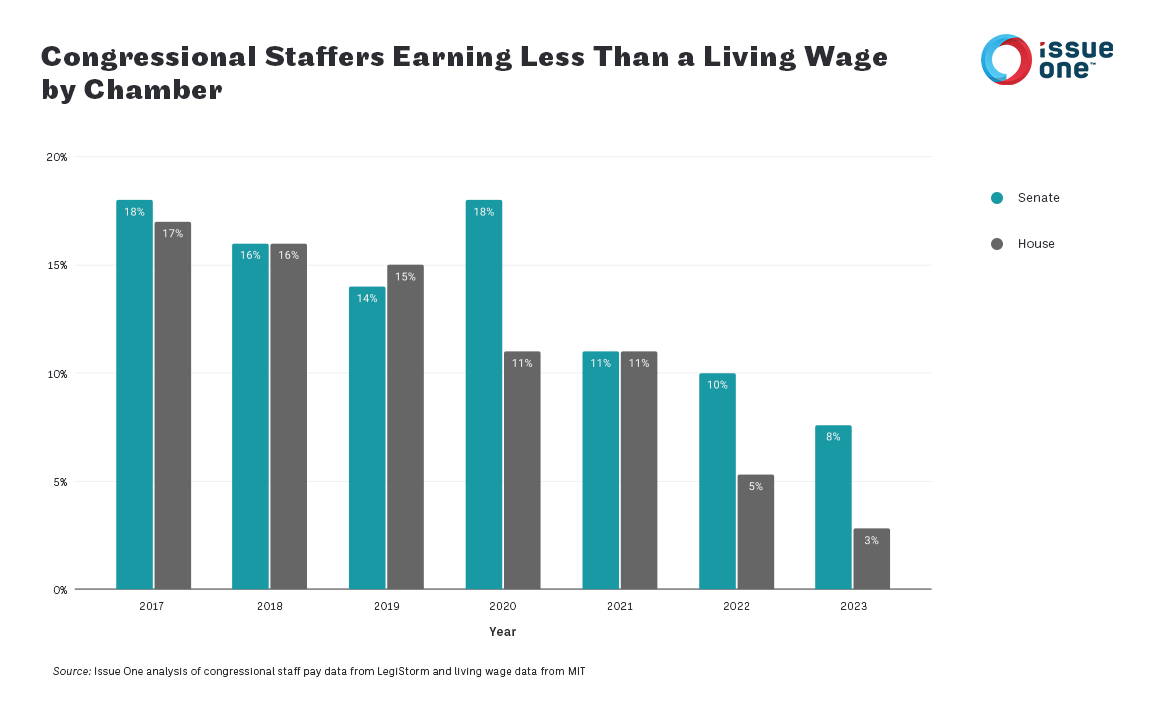

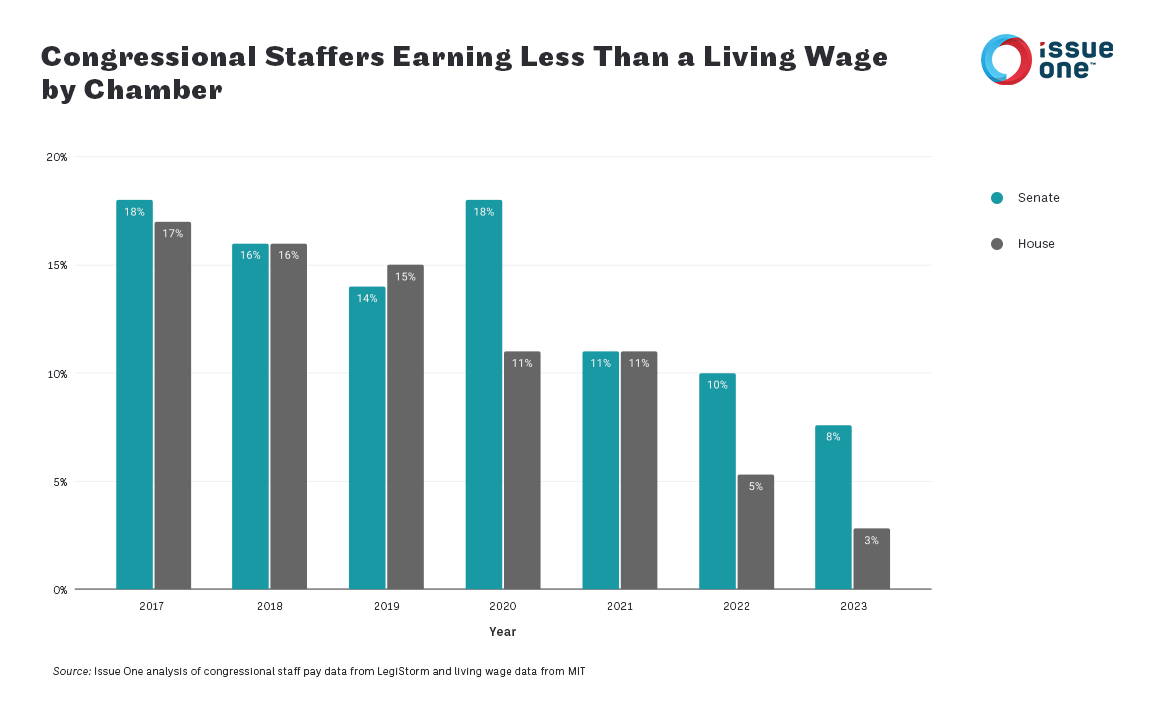

- More of this wage growth has been felt in the House of Representatives than in the Senate. In 2021, the year before the House instituted a pay floor, roughly the same portion of D.C.-based House and Senate staffers made less than a living wage — 11%. In 2023, 7.6% of Senate staffers still made below a living wage, but that was true for just 2.8% of House staffers.

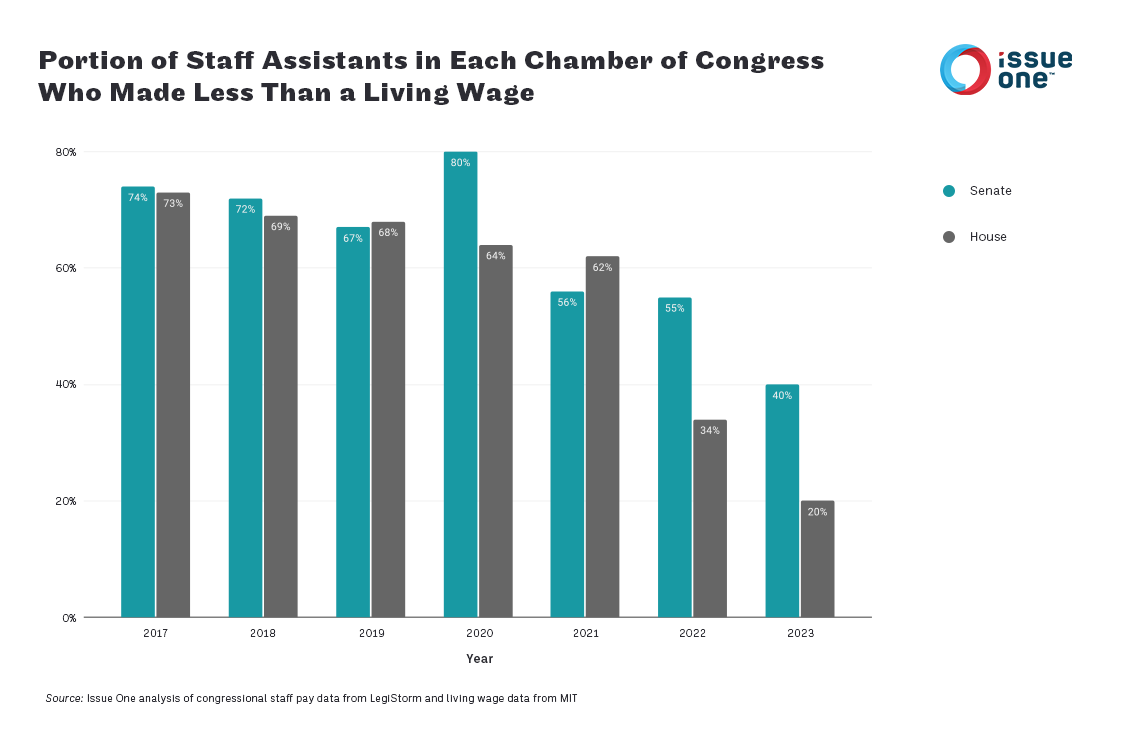

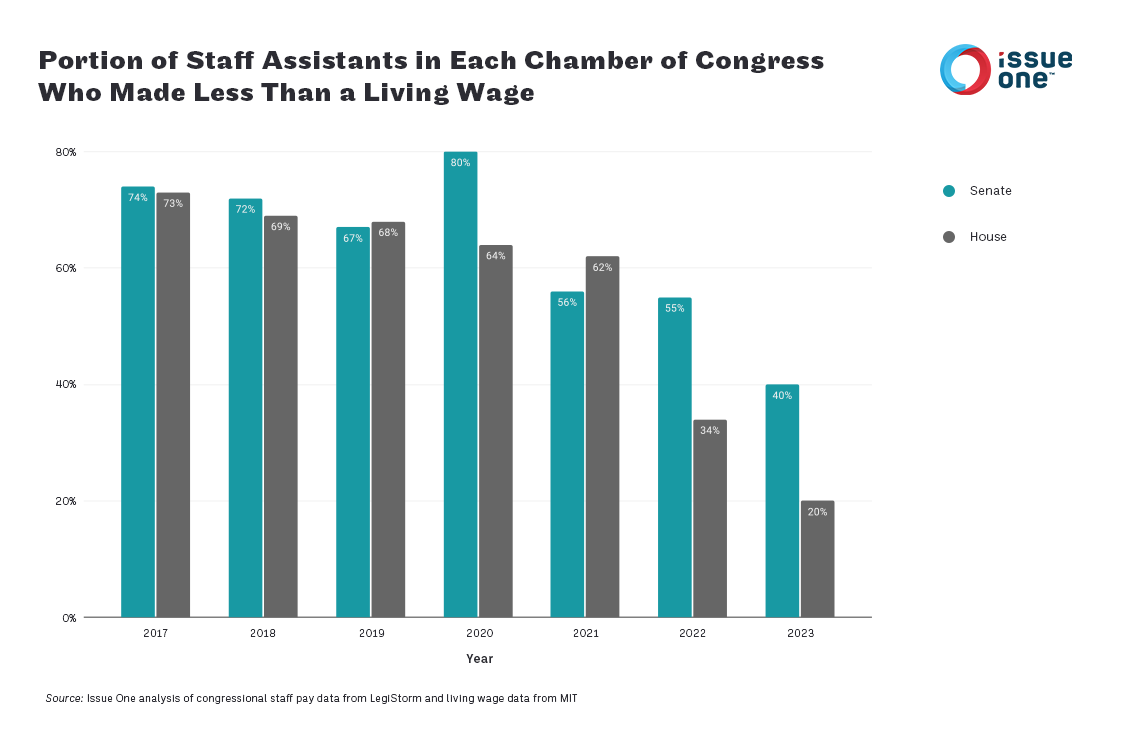

- Many staff assistants, typically the lowest-paid positions in Congress, are still struggling. While the typical staff assistant on Capitol Hill now makes more than a living wage, staff assistants in the House are faring better than their counterparts in the Senate, with the typical House staff assistant making roughly $4,500 more per year in 2023 than the typical Senate staff assistant. While the portion of congressional staff assistants making less than a living wage has fallen from 70% in 2020 to 28% in 2023, 40% of Senate staff assistants made less than a living wage in 2023 and the same was true for 20% House staff assistants.

How a Pay Floor Is Helping the House Outperform the Senate When It Comes to Staff Compensation

In January 2022, Issue One published a report showing that roughly one in eight congressional staffers in Washington, D.C., made less than a living wage in 2020, the most recent year for which congressional staff pay data was available. Among those not making a living wage were about 70% of staff assistants, the most common entry-level position on Capitol Hill, with every member of Congress having at least one.

According to researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), the living wage for a single adult with no children in Washington, D.C., was about $42,600 in 2020. It is important to note that a “living wage” is not an ideal salary, but rather a baseline. MIT’s researchers say that a living wage is best understood as a “minimum subsistence wage,” i.e., the amount needed to meet one’s basic needs such as housing, food, transportation, and medical expenses. It doesn’t allow for expenditures that many Americans consider normal parts of a good life, such as vacations, meals at restaurants, owning a car, or saving for retirement.

In May 2022, then-Speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) announced a higher pay scale for House staff, including a minimum $45,000 annual salary. This “pay floor” went into effect in September 2022. These moves came just months after congressional leaders agreed to a 21% increase in the Members’ Representational Allowance (MRA), which is allocated to fund House offices, including staff pay.

Congress hasn’t always been on the forefront of investing in its own institutional capacity. Between fiscal year 2010 and fiscal year 2013, the MRA was actually cut by more than 5% per year. And for much of the subsequent decade, the MRA remained flat or saw only modest increases. Over the same period, the allowance that senators receive for their offices — known as Senators’ Official Personnel and Office Expense Account (SOPOEA) — likewise saw a series of cuts followed by flatlined investments and then a few modest increases.

Issue One’s new analysis shows the portion of D.C.-based congressional staffers making less than a living wage was cut in half between 2021 and 2023 — and the typical congressional staff assistant now makes more than a living wage.

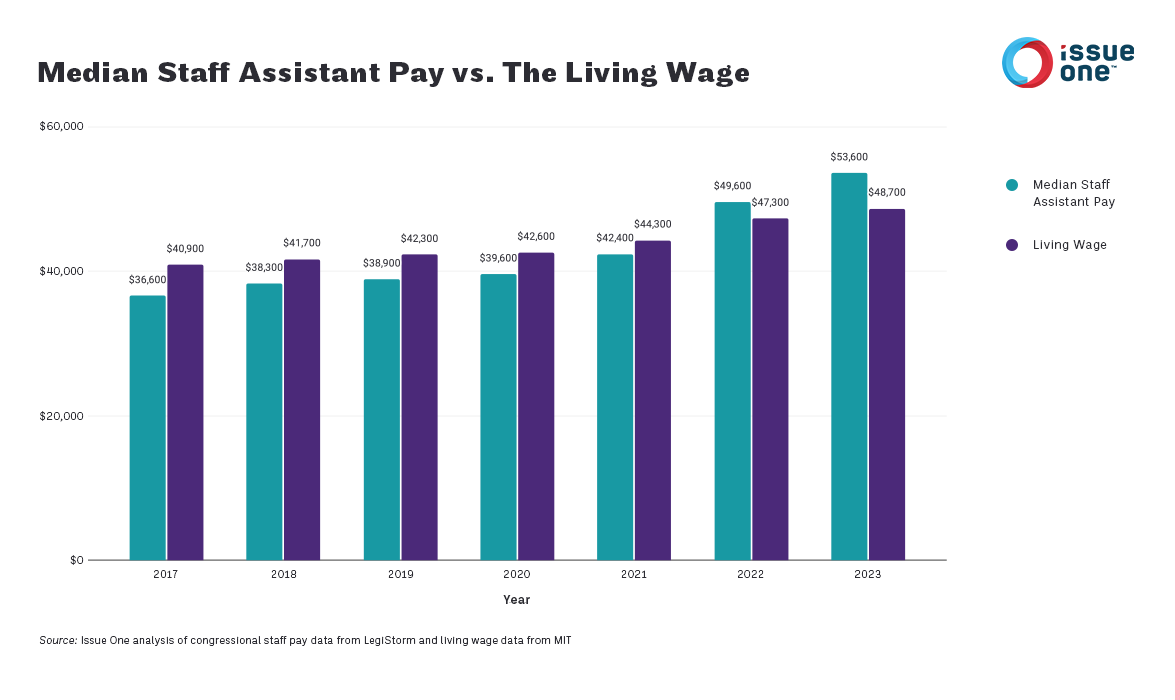

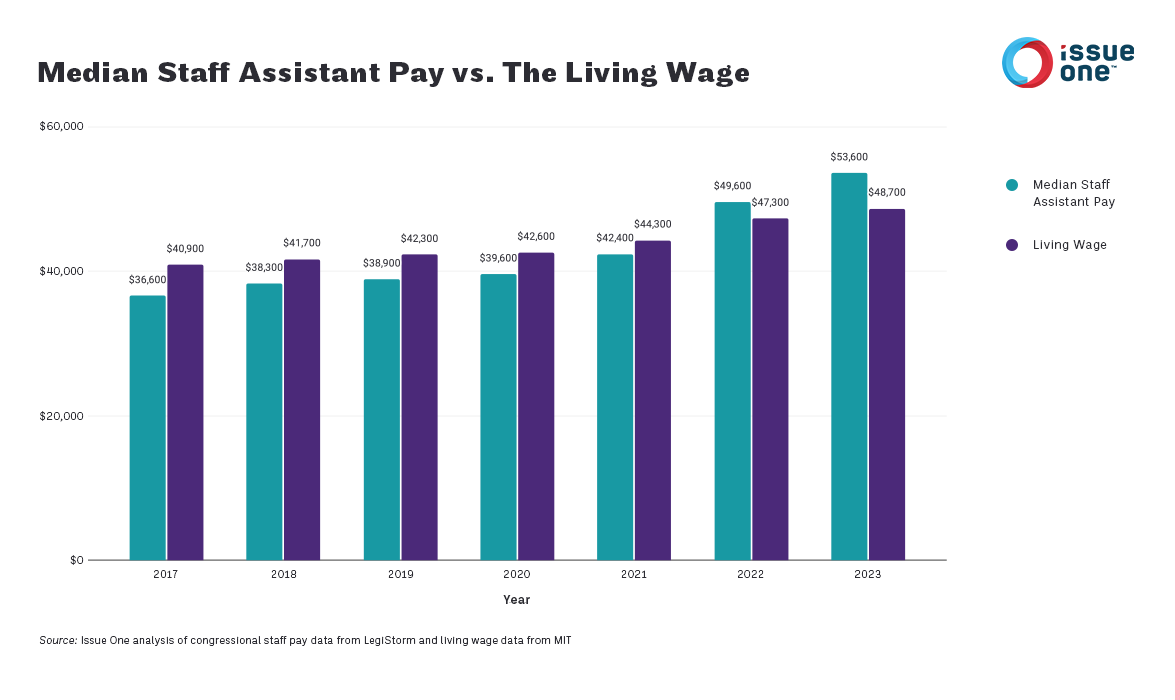

According to Issue One’s new analysis of congressional staff pay data provided by LegiStorm, just 4.6% of D.C.-based congressional staffers made less than a living wage in 2023. That’s down from 11% in 2021. And in 2023, the typical staff assistant on Capitol Hill made about $53,600 — nearly $5,000 more than the living wage.

This has come despite the fact that the amount of money needed to make a living wage has risen — from roughly $44,300 in 2021 to $48,700 in 2023 to $49,700 today.

This is thanks, at least in part, to the new pay floor in the House of Representatives.

More of this wage growth has been felt in the House of Representatives than in the Senate, which does not have a pay floor like the House does.

In 2021, roughly the same portion of House and Senate staffers made less than a living wage — 11%. In 2023, just 2.8% of D.C.-based House staffers made below the living wage. However, 7.6% of D.C.-based Senate staffers still made below a living wage in 2023.

Issue One’s new analysis of LegiStorm’s data further shows that the median salary of D.C.-based House staffers increased by about 7.9% between 2021 and 2023 (when adjusted for inflation). But the median salary of D.C.-based Senate staffers actually decreased by about 1% (when adjusted for inflation) during the same time.

Nevertheless, as recently as last year, only 58% of House staffers thought their current salary was enough to cover their living expenses, according to the official House Workforce Survey. As one surveyed staffer said: “After insurance and taxes, I barely have enough to pay my bills and am very close to the poverty level.”

Who Doesn’t Earn a Living Wage?

According to the 2023 House Workforce Survey, 57% of House staffers are 35 years old or younger, including 23% who are 25 years old or younger. Two-thirds of House staffers have worked for Congress for less than five years.

Many of the staffers earning the smallest sums are staff assistants or in other entry-level positions.

In 2021, the year before the House pay floor was implemented, nearly 60% of D.C.-based congressional staff assistants made less than a living wage. In 2023, that number dropped to 28%. It’s good news that the share of D.C.-based staff assistants making less than a living wage was cut in half between 2021 and 2023, though progress has been uneven across the two chambers of Congress and economic hardships remain very real for too many congressional staffers.

Issue One’s analysis of LegiStorm data shows that in the House of Representatives, 62% of D.C.-based staff assistants made less than a living wage in 2021. In 2023, just 20% did.

During this time, the median salary of D.C.-based staff assistants in the House increased by about 20% (adjusted for inflation), with the typical House staff assistant making about $55,200 in 2023.

Meanwhile, in the Senate — which does not yet have a pay floor — 56% of D.C.-based staff assistants made less than a living wage in 2021, and last year, about 40% did.

During this time, the median salary of D.C.-based staff assistants in the Senate increased by about 7.6% (adjusted for inflation), with the typical Senate staff assistant making about $50,700 in 2023.

Put another way: The typical House staff assistant now makes roughly $4,500 more per year than the typical Senate staff assistant. But the fact that nearly 30% staff assistants who work in the Capitol made less than a living wage in 2023 — including 40% of Senate staff assistants and 20% House staff assistants — shows there is still room for improvement and additional measures that will open the doors of opportunity to Americans from all socioeconomic backgrounds.

Fair Pay Can Help Congress Better Represent the Country

For our democracy to succeed, diverse perspectives and backgrounds must be reflected in the institutions that shape the nation’s laws. A livable wage is a reform that would strengthen the institution of Congress and make it more representative of the country it serves. Fair compensation for congressional staff — and interns — will help Congress attract and retain a diverse and skilled workforce, from a variety of socioeconomic and racial backgrounds.

In part because of a disparity in access to financial resources, the halls of Congress today generally lack a staff that is representative of the United States, especially among top staff. For too long, those best able to gain access to low-paying entry-level positions on Capitol Hill have come from affluent families, where low wages could be supplemented by financial assistance from relatives. And historically, people of color have had less access to the financial resources available to many white families. For instance, for every $100 in wealth held by white households in the United States in 2022, Black households held only $15, according to the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances. And the difference between the wealth of the median white household in the United States in 2022 and the median Black household was $240,000.

According to data from the Census Bureau and the House Workforce Survey, people of color accounted for about 42% of the U.S. population in 2022 but just 30% of House staffers in 2023. Similar data about all Senate staffers is not available, though anecdotal evidence and analyses of staffers in senior positions suggests disparities also exist in that chamber of Congress.

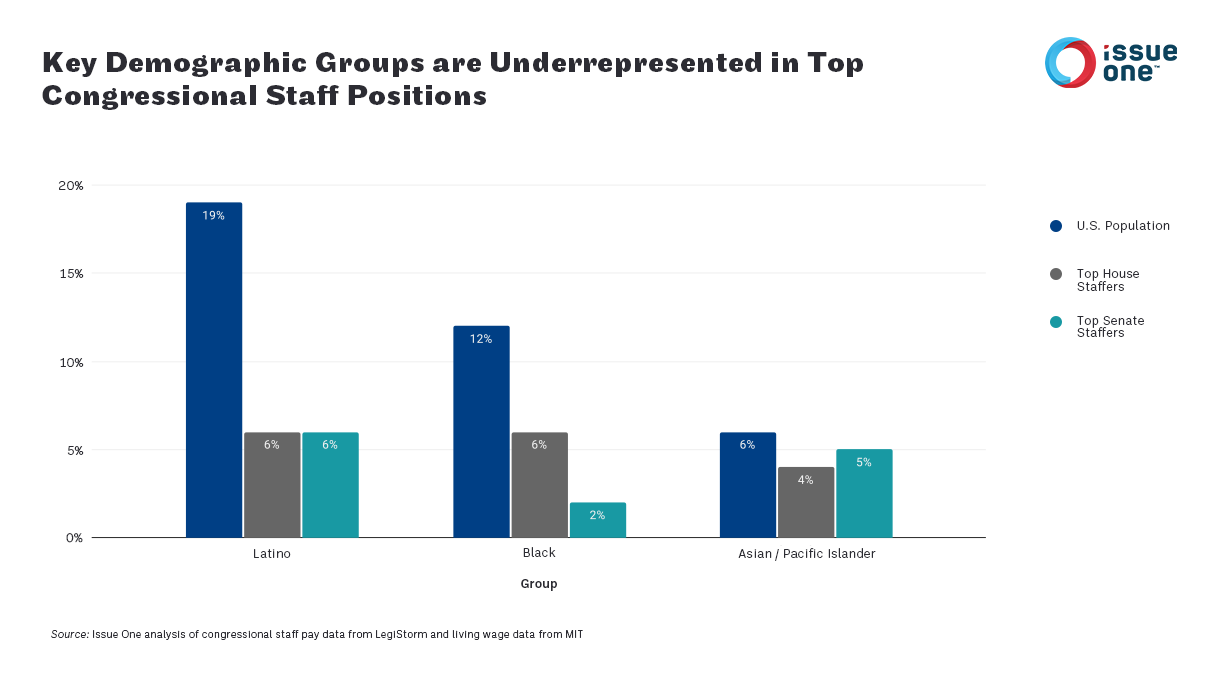

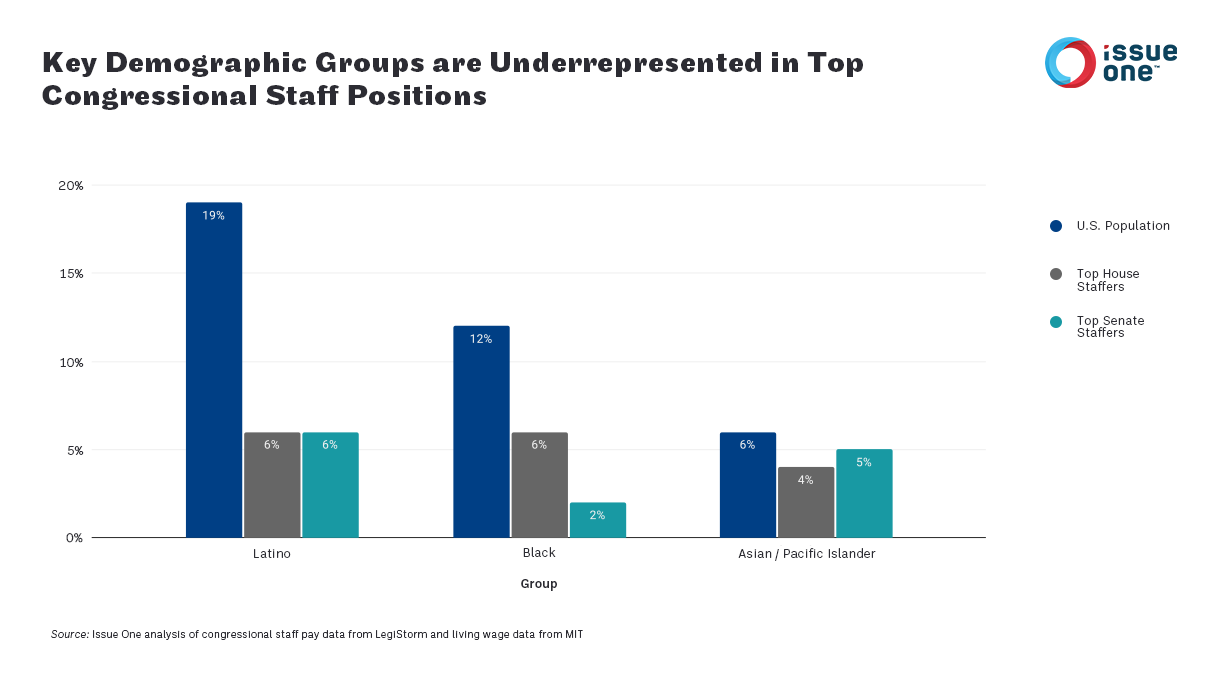

According to the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, which analyzed the demographics of top House staffers in 2022 and top Senate staffers in 2023, just 18% of all top House staffers were people of color in 2022 and only 16% of all top staffers in senators’ offices in 2023 were people of color. Several demographics are woefully underrepresented.

While about 12% of the U.S. population is Black, the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies found that just 6% of top House staffers in 2022 were Black and only 2% of top Senate staffers in 2023 were.

Similarly, while about 19% of the U.S. population has Latin American heritage, just 6% of top House staffers in 2022 had such heritage and just 6% of top Senate staffers in 2023 did.

Meanwhile, the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies found that Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders accounted for about 4% of top House staffers in 2022 and 5% of top Senate staffers in 2023, slightly below the roughly 6% of the U.S. population that such individuals account for.

As of June 2023, at least half of senior congressional staffers were people of color in less than 20% of House member’s offices and in just 12 senators’ offices, according to the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies.

For junior and senior staffers alike, positions on the Hill can mean long hours with wages lower than the private sector.

Last year, 81% of senior congressional staffers surveyed by the Congressional Management Foundation reported feeling overwhelmed by the demands of their jobs, and 84% reported frustration at not being able to help or achieve as much as they’d like. The Congressional Management Foundation warned that these are factors “which may lead to burnout.” And according to the 2023 House Workforce Survey, 43% of House staffers reported often feeling burnout because of their job. The House Workforce Survey also found that the No. 1 reason employees considered new career opportunities was that they needed “better pay and benefits.”

Better-paid staff who feel valued are more likely to stay, which can halt the brain drain in Congress and reduce the influence of lobbyists and special interests. Advocates across the political spectrum have long warned how a brain drain among congressional staffers hinders Congress’ ability to govern as effectively and efficiently as possible. Competitive salaries are necessary to retain staff of all walks of life in these important roles on Capitol Hill.

Building a pipeline of talented congressional staffers from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds should also involve financial investments in internships on Capitol Hill. According to the 2023 House Workforce Survey, 43% of House staffers began their congressional career through an internship or fellowship. Before 2017, only 10% of congressional interns were paid.

In 2018, Congress passed a bill specifically allocating funds for lawmakers to pay their interns, awarding $20,000 to each House office and an average of $50,000 per Senate office for D.C. intern stipends. And in 2021, acting on a recommendation of the bipartisan Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress, the House began allocating money to pay interns who work for House committees. Yet a report by the advocacy group Pay Our Interns found that the average pay for a Senate intern in 2019 was about $10.14 per hour — and the average pay for a House intern in 2019 was about $4.62 per hour.

How Congress Should Build on This Progress

Congressional staff salaries generally remain well below competitive salaries for similar positions in the private sector. Yet competitive pay is essential to maintaining institutional knowledge and enhancing the efficiency of Congress in meeting the evolving needs of constituents as well as navigating policy-making challenges.

Here are seven policies and practices that Congress should implement now to help improve staff pay and retention.

- Institute a Livable Pay Floor for Full-Time Workers in the Senate: Congress must ensure that all staff receive a fair and livable wage. Following the lead of the House of Representatives, the Senate should also establish a pay floor for its full-time staffers. This will ensure that all staffers in both chambers of Congress earn a living wage. And until an official policy change is adopted, each member of Congress should voluntarily implement the practice of paying each of their staffers a living wage.

- Index Congressional Pay Floors to Inflation: Funding for the Members’ Representational Allowance and Senators’ Official Personnel and Office Expense Accounts have consistently lagged behind inflation, and when the House of Representatives established its $45,000 pay floor in 2022, it wasn’t indexed to inflation. If it had been indexed to inflation, the pay floor would now be approximately $47,300. Indexing congressional pay floors to inflation would help junior staff avoid being squeezed by inflationary pressures in the future.

- Issue Paychecks More Frequently: A small but mighty reform that would aid cash-strapped House staffers is changing how paychecks are issued. House staff are currently paid once a month. This is out of sync with how Senate staffers are paid, and, indeed, with how most Americans are compensated. By issuing paychecks either every other week or twice a month, staffers would have quicker access to their wages, providing increased financial flexibility, especially for emergencies. The idea of issuing paychecks on a semimonthly basis was endorsed by the bipartisan Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress, and Reps. Derek Kilmer (D-WA) and William Timmons (R-SC), the former chair and ranking members of this committee, have introduced bipartisan legislation to enact this commonsense change. The House would be wise to quickly adopt it.

- Pay All Congressional Interns: Internships are crucial pathways to formal jobs in Congress. Since 2018, more than $133 million has been allocated to specifically fund congressional internships, though lawmakers are not required to pay their interns. The latest congressional appropriations bill, which was signed into law in March 2024, specifically included $24 million for paid internships in the House and $7 million for paid internships in the Senate. As congressional leaders debate spending levels for the next fiscal year, these investments in paid internships should be protected and increased.

- Support Professional Development Initiatives: Support for professional development opportunities should continue in both chambers of Congress, including mentorship and training programs, so that staff are empowered to grow in their positions and forge the strongest possible connections with their colleagues. One aspect of this would be reestablishing the House Office of Diversity and Inclusion, which was created in March 2020 as the result of a recommendation by the bipartisan Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress but disbanded in March 2024. The office offered a host of services, including resume review workshops, professional development programs, and organizing career fairs to help connect a diverse talent pool to job opportunities in Congress. Reestablishing the House Office of Diversity and Inclusion — and creating a counterpart in the Senate — would help develop and support a congressional workforce that reflects the makeup of the nation.

- Members of Congress Should Make Full Use of the MRA and SOPOEA: Individual legislators have significant latitude in how they structure their offices, including what positions they hire for and the compensation of those positions. Lawmakers should fully use their MRA and SOPEA funding to help them do the jobs they were elected to do. Over the years, members of Congress ranging from Sens. Joe Manchin (D-WV), Rand Paul (R-KY), and Jacky Rosen (D-NV) to Reps. Andy Kim (D-NJ), Dan Meuser (R-PA), and Daniel Webster (R-FL) have boasted about not spending their full office budgets and returning unspent dollars to the Treasury. Yet when members of Congress performatively attempt to “virtue signal” by returning unspent congressional office funds, that actually hurts their own staffers and the public. If every member of Congress were to utilize their resources fully, it would both enhance staff pay and also increase the overall effectiveness of their congressional offices.

- Continued Institutional Investments: The 21% increase in House office budgets in fiscal year 2022 helped enable increased staff pay. Continued investments in congressional capacity, including the pay of interns and junior staff, will help strengthen our country’s democratic institutions and foster a healthier workforce within the legislative branch of government. In 2023, the MRA saw a modest increase of 4.6% — an investment that 40 former members of Congress who are part of Issue One’s ReFormers Caucus praised Congress for adopting. The latest congressional appropriations bill, which was signed into law in March 2024, included a roughly 7.9% increase to senators’ SOPOEA office budgets but kept funding levels for House offices flat, even as inflation rose about 3% in the Washington, D.C., area, between 2022 and 2023. As congressional leaders debate spending levels for the next fiscal year, additional investments in lawmakers’ office budgets shouldn’t be neglected. When Congress routinely and meaningfully invests in itself, it helps ensure that knowledgeable public-service minded staffers are helping create policy to benefit all Americans.

Arianna Nassiri contributed to this report.

Methodology: How We Did This Analysis

For this analysis, we used the living wage calculator created by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to find the current living wage estimate for a single adult with no children in Washington, D.C. These researchers told us that their model has improved over time as data sources and calculations improve, so we then adjusted the current living wage of $49,714 for inflation utilizing the Consumer Price Index values from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics specific to the Washington, D.C., region, calculating what this wage would have been in 2023 dollars, 2022 dollars, etc., going back to 2017 dollars. This approach allows us to use the most robust and up-to-date living wage estimate. Congressional staff pay figures came from an Issue One analysis of data from LegiStorm, omitting interns, fellows, and staff shared by multiple members of Congress.

Photo: Tim Mossholder/Unsplash

Photo: Tim Mossholder/Unsplash